Black brain drain causes many African American professionals to move abroad. Why?

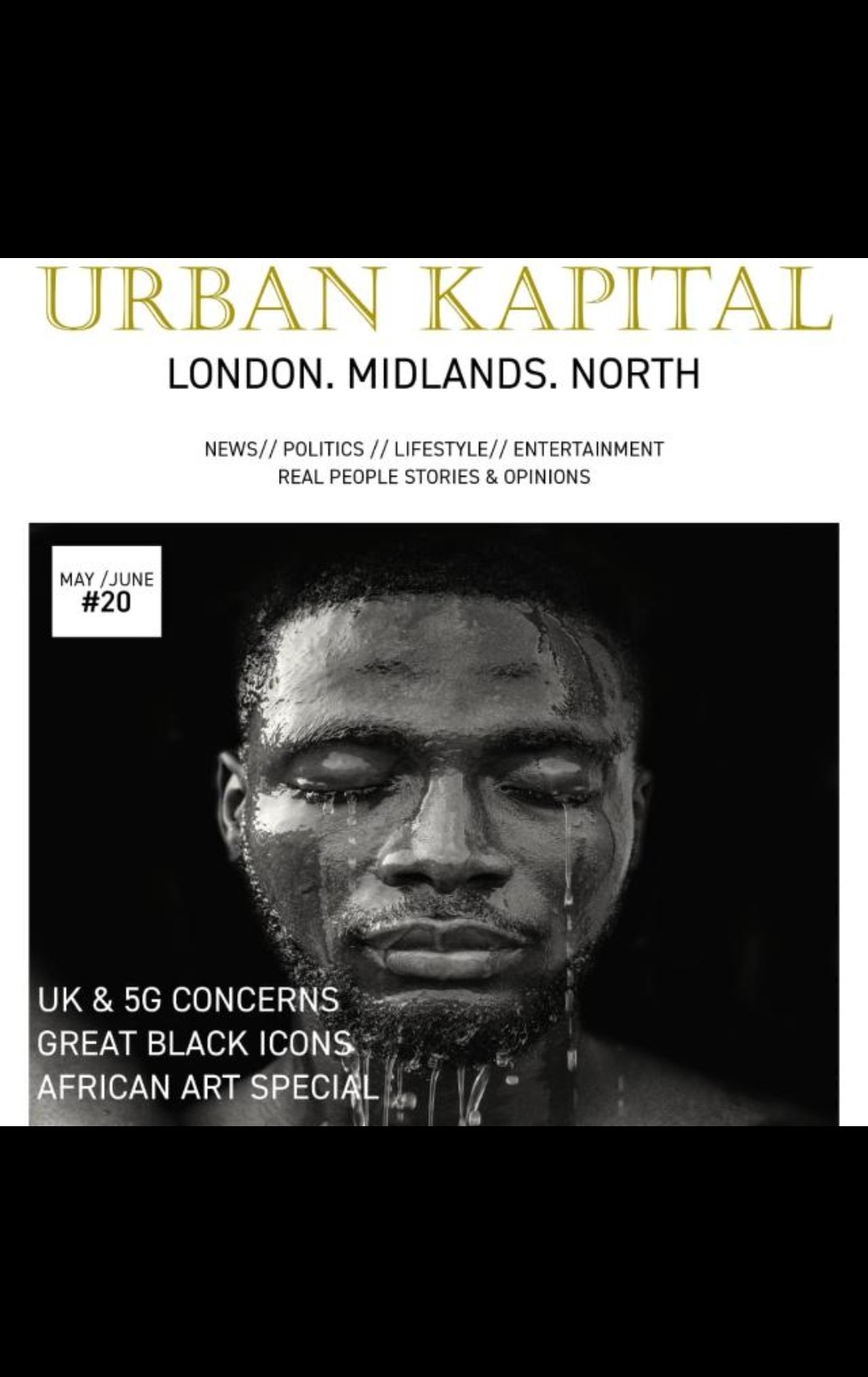

- Urban Kapital

- Aug 10, 2020

- 11 min read

It was 2013, and Najoh Tita-Reid, then an executive at pharmaceutical giant Merck, was in the midst of the interview process for a job that would send her on her first international assignment. During a break in the conversation, “a white gentleman pulled me aside,” she says, and told her that all of the white men up for the role were “selling that they’d conquered the moon”—while she was focused on explaining what she saw as the weak spots in her résumé. If Tita-Reid wanted the position, he said, she would need to turn everything she had into an asset. So she went back into the interview and laid out her biggest selling point: She was the best person for the job because she was a Black woman in the United States. She was used to being the only person in the room who looked like her. The “cultural competency” the hiring managers were looking for was not a skill she’d had to learn for work; it was something she’d had to master to just get by in her everyday life. “I can get the nuances of every culture because this is what you have to do as an African-American,” she told them. “You have to shape-shift to survive.” She sold it, she says, “and it was all true.”

Tita-Reid got the promotion, running Western Europe for the company out of London. Seven years later, she’s still living and working abroad—now in Switzerland, where she holds a global marketing job for Logitech. And, at least for now, she has no plans to return to the U.S.

Like many of corporate America’s ladder climbers, Tita-Reid first went after an international role with the goal of enhancing her career. But in the years since she made that first move to London, she’s become part of a cohort of Black American expats who have chosen to stay abroad because they’ve found that the professional benefits of working overseas are far more profound than the usual résumé-building check mark. Working in Europe, Tita-Reid says, has been like wearing an oxygen mask. It’s allowed her to breathe—to lead and perform without feeling the crushing weight of America’s dysfunctional racial dynamics at every moment.

I'd never been an American first and then Black. It's a refreshing change.

With her friends, Tita-Reid calls it the “James and Josephine effect”—a hat tip to James Baldwin and Josephine Baker, Black Americans who fled the racial persecution of the U.S. during the first half of the 20th century and ended up with thriving careers in Europe. “It’s not a new phenomenon at all,” she says. “I feel like part of that legacy.”

The decision to work and live abroad has been brought into sharp relief for many Black American expats this spring and summer as they watch a national movement take hold back home in the aftermath of the police killing of George Floyd. There’s a sense of guilt at not being on the front lines, mixed with affirmation of why they did not want to return.

Working abroad, these executives say they left behind the fatigue that many described as routine for Black people in corporate America: the exhaustion brought about by being asked to solve your company’s diversity issues; living by the unwritten rules that dictate how you present yourself at work; having to prove every day that you deserve to be in your role. Once abroad, with the weight of their companies behind them, many Black expatriates said they felt instantly valued and treated with a level of respect and deference from their colleagues they had not known in the U.S.

The benefits extend far beyond the office. The prevailing message in more than a dozen interviews with Black Americans who are working or have worked overseas: Their international experience was the first-time race was not the primary frame of reference through which they were viewed. “You’re an American, you’re not African-American,” says Shaundra Clay, who lived in Europe for eight years as a healthcare executive. “You are not made to feel like you are carrying the burden of anything. You are carrying the power of something.” She said it was a level of privilege she had never experienced before in her life. In the U.S., Nancy Armand, an executive at HSBC Bank USA, was always conscious of her gender and race, she says. In the U.K., she was always conscious of her nationality first. “I’d never been an American first and then Black,” Armand says. “It’s a refreshing change.”

And yet these jobs can be isolating. Rarely does Tita-Reid see another Black woman at her level. “On a day-to-day basis,” she says, “I am alone.” That’s in part because the expat universe is running 20 to 30 years behind the larger corporate world in terms of diversity and inclusion, says Adrian Anderson, a partner in KPMG’s global mobility services. He has both personal and professional experience here: For more than 25 years, Anderson has worked in the industry, which helps multinational organizations manage their workforces’ foreign assignments; he has also lived abroad as a Black American executive. Most of these coveted international roles come through word-of-mouth networks, which have historically boxed out Black employees. Or they are reserved for developing those expected to move into the executive suite—a space that has also long passed over Black talent. Anderson says most global organizations prefer that executives have international experience in order to move into top-level roles, making the lack of access to the expat world a systemic barrier that has kept Black employees from reaching the top echelons of corporate America.

Black executives who pack their bags and leave the U.S. behind are quick to point out that they are by no means moving to any sort of utopia. “I’m very clear that wherever I go, I’m perceived as a Black man,” says Warren Reid, Tita-Reid’s husband and founder and CEO of Nemnet Minority Recruitment, a diversity recruitment and consulting firm that works with educational institutions. “Unfortunately, in the overwhelming majority of the globe, I don’t have a positive brand image. I’m mindful and not naive about that.” Despite such awareness, Reid and others interviewed for this story said they had not realized how heavily the stress of being Black in America weighed on them until they left. Even when they faced bias abroad, they never feared for their lives or their children’s the way they did in the U.S. Says Ini Archibong, a designer and business owner originally from California who now lives in Switzerland: “The brand of racism in America is unique.”

In corporate America, Black executives are used to having to tell people they’re the boss. Otherwise, says Tita-Reid: “When you walk into a room in the U.S. and you are five levels above your sales rep who’s a white man, they look at him and shake his hand and give you the bag.” But soon after transferring to the U.K., she had a meeting with a client who immediately identified her as the person in charge. “You’re a Black American female, and you’re here, so you have to be the best,” she recalls him saying. It was the first time anyone had labeled her the “best” at anything, she says. “I almost cried.” Reid distills the dynamic this way: In the U.S., he says, the question is always, How did you get in the room, and who let you in? In the U.K., the assumption is that if you’ve made it into the room you deserve to be there.

But working in Europe means adjusting to more subtle forms of racial prejudice—which often intersect with a strong vein of classism, say many Black execs who have done tours abroad.

Arlene Isaacs-Lowe, a 22-year vet of Moody’s, transferred to the U.K. in 2015 to run relationship management for Europe, the Middle East, and Africa for the ratings agency. The day she met her new U.K. team, she recalls being repeatedly introduced as an alumna of Howard University and a board member of its business school, followed by a recitation of Howard’s famous alumni. It stuck her as odd, she says, until she realized it was a way of establishing the bona fides of the historically Black university—and by extension, proving her “pedigree” as fellow member of the upper class.

Once that fear lifted from me, I realized I was never going to move back.

In 2017, Tita-Reid joined a health food company as global CMO, and the family moved to Switzerland. In her new home, nationalism was the dominant force, she says. Swiss people support Swiss people first, she says: “If you don’t happen to be of that culture, it has nothing to do with you.” She recalls a conversation with a German businessman, who felt that there was bias against his nationality throughout the country. To Tita-Reid, it was a relief that everyone was considered an outsider. “We’re all equal-opportunity excluded,” she says. “To me, that’s amazing. It’s the first time I’ve ever been equally excluded.” She explained to the businessman that unlike when he returned to Germany and felt accepted, when she went back to the U.S., she still felt like an outsider. “The negativity of being an American in Europe is not as bad as being a Black American in America,” she says.

Three years ago, Tita-Reid had a chance at a job that would take her back to the U.S., but she turned it down. It wasn’t just a career decision but one for her family. “The stress that I felt in the U.S. and concern for my husband and son was gone,” she says. “It was more of a weight than I had ever realized.”

I spoke to Reid over Zoom, where he sat outside their Zurich home on a sunny day with birds chirping in the background. He told me about the family’s first night in London when they were living in temporary housing. He was going back and forth between the hotel and the flat late at night when he saw two police officers walking toward him. “I remember in that moment, I went through my mental checklist of no sudden moves, communicate, make sure you’re seen.” The police officers walked past him with nothing more than a good night. “That blew my mind,” he said.

After we talked, Reid sent me a follow-up email, quoting James Baldwin: “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost, almost all of the time.” Living abroad, Reid was free of that rage, he said: “It does not consume or preoccupy me in the way that it did and does when I return home.”

For Dimitry Léger, the narrative of the Black American expat who thrives abroad holds true—until you want to get hired by a European company. If you have the wealth of America behind you, “you are welcomed with open arms,” he says. “When you ask for a job, things change.”

Léger made the move abroad 15 years ago. His then-wife is Swedish and wanted to live closer to her family, and Léger had always been intrigued by the idea of an international career. In 2004, he left journalism behind to get a graduate degree in international relations at Harvard, and the following year ended up in Geneva with the World Economic Forum as a partnership and communications manager. (Léger worked at Fortune from 1999 to 2002, but we never overlapped.)

Over a decade, Léger says he tried repeatedly to secure a full-time role with the UN, or as a corporate communications executive with a multinational company. Léger, who is Haitian-American and speaks both English and French, says at the UN he was repeatedly passed over; the jobs ended up going to Brits who were not perfectly bilingual—a supposed prerequisite for those roles. In the corporate world, interviews abounded, but he says the leads would turn cold once he showed up in person. One would-be employer went as far as explicitly citing his race as an issue, he says, telling him, “Our investors will have a problem with a Black spokesperson.” Eventually Léger started following the European practice of putting his photo on his résumé to spare himself the grief. Once he did, even the interviews dried up.

Léger attributes part of his struggle to a lack of formal or informal support structures. The number of top Black executives in the U.S. is woeful, but in Europe Léger found the situation to be far worse. “There are no senior Black executives anywhere,” he says, “so there’s no network of us to look out for each other.” Several Black men, including Léger, told me it was often assumed that they were visitors, because otherwise how could they be eating in this fancy restaurant in this nice part of town?

Now, with his oldest child thinking about attending college in the U.S., Léger was back in New York, living in Midtown Manhattan. When we spoke in June, he was regularly encountering the Black Lives Matter protests in the city and feeling nervous every time he saw a police car. “I did not miss that,” he says. But he was still glad to be home. “I like my odds of finding a stable full-time job in media,” he says, “of getting the job that eluded me in Europe, even in the middle of a pandemic and the ongoing fight for racial justice here.”

One of the major downsides of transferring abroad is the struggle that comes with moving back. All of a sudden, executives’ worlds felt much smaller, their jobs narrower. Clay returned to the U.S. in 2016 after eight years in Europe. She described the experience as akin to going back to your hometown after decades away, and having your successes celebrated but no one fully understanding how much you have grown and changed.

But for Black Americans, repatriation also came with unique baggage. Clay said the racism she had always seen and experienced in the U.S. now emerged with a different sense of clarity. “The longer you’re away, the more stinging and shocking it becomes,” she said. “All the burdens become your burdens again, and they feel heavier because you’ve lost the muscle of carrying them.” She and others I spoke to said they now had less tolerance for the racism they regularly experienced.

Those who have remained abroad have faced their own new personal struggles this spring and summer, describing feelings of deep conflict in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd and protests that have followed. Reid says by being abroad he’s meeting his primary obligation to provide a safe and affirming environment for his family; his children have not had to wrestle with some of the issues he did as a Black kid growing up in the U.S. “That’s been the good side,” he says. “The other side is there is a movement that’s going on, and I’m removed from it. There’s a little guilt that goes along with it: How could I bring to bear my education, resources, and network to move the movement forward?”

Archibong, the American designer based in Switzerland, says it’s difficult not to be in the U.S. right now. But while Switzerland has its own problems, he says, it’s not enough to make him want to go back. The power of escaping that constant existential fear described by so many of the Black American executives I spoke to is too strong. “Once that fear lifted from me, I realized I was never going to move back,” he says. Not being constantly concerned with his physical safety has allowed him to “clear up space” in his head and be more creative in his work. A few years into his move to Europe, Archibong stopped wearing the collared shirts he’d long worn every day—even if it meant being overdressed for the occasion. The formal look had started as an aesthetic choice, he says, but at some point he realized it had become a kind of armor. In the U.S., he’d felt safer when he was dressed up, he says, and the dressier clothes had helped him command the same professional respect that other, non-Black designers got even when casually attired. In Switzerland, he no longer feels the need; now he pulls out the suit and tie only when he’s in the mood.

Tita-Reid struggled to articulate what it’s been like watching the current movement in the U.S. from afar. She, like her husband, says she feels somewhat guilty that she’s an ocean away. It has been both sad and validating to see all of the concerns that had kept her from wanting to return bubble up to the surface. It’s also made her acutely aware of all the good things she had left behind. “You do give up something, which is having your culture, your people, your friends and family,” Tita-Reid says. “It’s at a cost.”

Specifically, 77% of experts say Black executives have less access to global assignments, contributing to the systemic bias that Black professionals face in corporate America. 41% employers are now focusing on ensuring that international assignments don’t exclude women and people of color, but it’s still a long way from being a top priority for most. 20% of companies see a decrease in international moves as a result of COVID-19. This shift could have an outsize impact on Black executives, who are already less likely to land foreign assignments because of the informal way they are doled out.

Source: Fortune

Commentaires