Britain’s equality watchdog ineffectiveness shown up by the Black Lives Matter movement

The ineffectiveness of Britain’s equality watchdog, which does not have a single black commissioner, has been shown up by the Black Lives Matter movement.

Even before this year’s historic Black Lives Matter movement, and the Covid-19 tragedy with its disproportionate impact on Britain’s ethnic minorities, everyone deep inside was impatient for deep structural change to tackle race inequality. So when the outgoing head of Britain’s equality watchdog, David Isaac, said that the government is “dragging its feet” over tackling racism, it was difficult to disagree.

However, Isaac is facing criticism over his own record on race during his four years as chairman of the Equality and Human Rights Commission. At a time when Black Lives Matter has stirred the nation, the EHRC has seemingly had little to contribute. Among its 10 commissioners it has not a single Black or Muslim member, and many people believe it should have investigated alleged Islamophobia within the Conservative party as it has rightly done over alleged Labour antisemitism.

Lord Woolley, director of Operation Black Vote, was also one of the EHRC’s last black commissioners – he left in 2012. And he has seen how its budget has been repeatedly slashed – from £70m at its launch in 2007, to just £17m today. It emerged from the joining together of three equalities groups – the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE), the Disability Rights Commission and the Equal Opportunities Commission (which looked after sex discrimination).

But its remit was also to enforce equality laws on age, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, religion or belief, and sexual orientation, plus human rights. Today, it has less to spend on all of these than the CRE had for race alone in its final year.

There is little doubt that the EHRC has been very poor in confronting race inequality for some years. Yet, before we get too emboldened about attacking it, we need to be careful how this could play out with those who would leap at the chance to close this potentially powerful institution down, and thus remove one of the few instruments of “independent” scrutiny on racism that we have left.

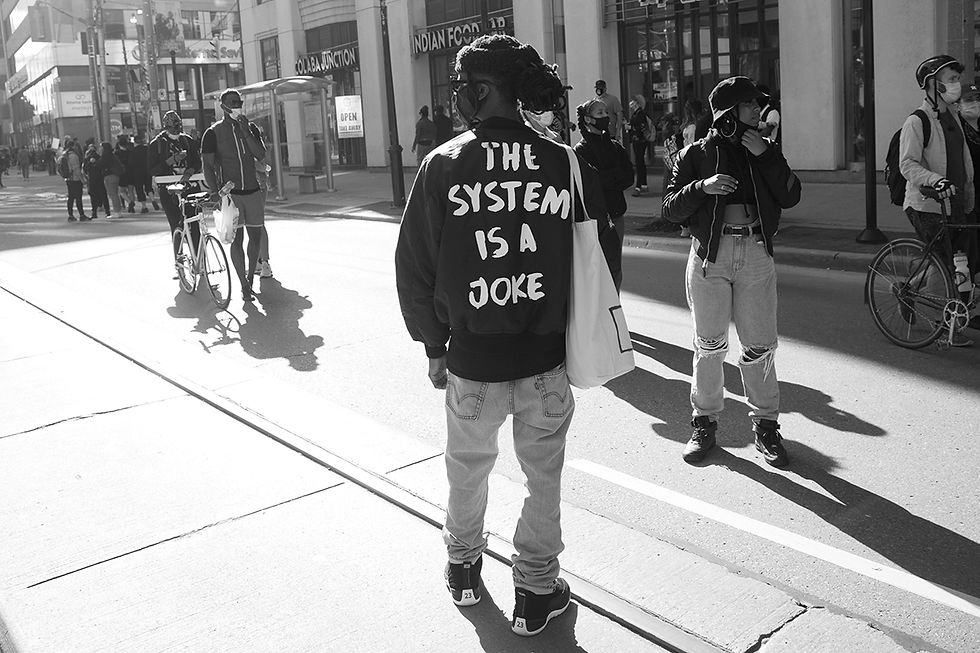

Lord Woolley has been particularly stuck by the huge gulf between the EHRC and the new generation of young Black Lives Matter activists. Recent governments, the commission and we as a society have badly let down this generation. The sustained protests since the death of George Floyd have not come out of nowhere. The generation is acutely aware of systemic and, in some areas, growing racism around policing, jobs and education.

The comments of one young man particularly were surprising: “In year 6, my main teacher approached me and my friend, who was black, and said: ‘When you’re older, please don’t join a gang.’ I replied: ‘We’re not going to join a gang,’ but it wasn’t until I started growing up that I began thinking to myself, what did she actually mean by that remark?”

Therefore now, more than ever, we need a strong EHRC with a particular robust component to deal with race inequality.

The contrast with the old CRE, under the leadership of Lord Herman Ouseley, a fearless independent advocate for race equality, is stark. Trevor Phillips’ style, in overseeing the transition from the CRE to the new commission, was more maverick but still he was afforded much independence.

Some of our best work together when he joined the EHRC was taking on the BNP and its racist membership policy. Another successful campaign at that time was, in 2010, to challenge the policing stop and search practices.

He remembers being called in to a meeting with the policing minister at the time, furious because he thought our recommendations would stop the police doing their job (they wouldn’t).

But by then, the writing was on the wall. The Tory-Lib Dem coalition seemed not to tolerate an independent commission that followed the evidence to target systemic biases.

And in 2012, Lord Woolley was informed that his contract, along with that of another race equality “troublemaker”, Baroness Meral Hussein-Ece, would not be extended despite the fact that our yearly evaluations were excellent. When he left there were plans to cut its staff from 500 to about 125.

For some time, the EHRC has lost much of its budget, its expertise and its enforcement abilities.

What happens next is anyone’s guess. But if the present No 10 mantra prevails, and appointments to these roles are according to loyalty to the party leadership – and that will soon become apparent – then the independence that is needed to head a body like this will vanish.

The high point of Britain’s race equality was establishing the Race Relations Amendment Act in 2000 after the previous year’s Macpherson report into the death of Stephen Lawrence.

This year has been the most monumental for British race relations since then. The next chair of the EHRC needs to be someone who can embrace the continuing Black Lives Matter moment and use it to break down the barriers of prejudice and inequality that are holding so many people back. Given the dire state of our economy, now more than ever Britain needs to unleash this huge pool of talent and potential.

Source: The Guardian, Simon Woolley

Comments